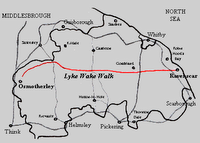

Camel wrestling at Selçuk, Turkey

Close to Ephesus, is the small town of Selçuk (pronounced Selchuk in Turkish). The place draws fewer visitors than its more well known neighbour, though it has its attractions.

Close to Ephesus, is the small town of Selçuk (pronounced Selchuk in Turkish). The place draws fewer visitors than its more well known neighbour, though it has its attractions.One of these is the camel wrestling festival every winter, an event that largely goes unnoticed by tourists, most probably because it takes place in winter when few are prepared to move from cold Northern Europe to a place that can be just as cold, Anatolia.

Winter is the mating season for camels, and so would coincide with their desire to fight off males looking for mates. It is also the time when the growing season is halted by snows, and so nomads forced down to lower pastures would provide or look for some form of sport and entertainment, camel wrestling provided both, as well as being a way to earn money.

Owning a winning camel in nomadic and village life is a way of gaining a certain notoriety; men defer to winning owners, children admire such men, and women vie for their attention, it is said.

The camels are given names like Thunderbolt and Destiny, though I didn’t hear them for the roar of the huge crowd on the cold winter’s day when I went along, diverted by chance from my visit to Ephesus; the bus I was traveling on broke down in Selçuk, and I alighted in the middle of the parade through the middle of the town.

Of course, any large gathering of men in Turkey is an excuse to eat and drink and be convivial; the parade of camels in Selçuk is no exception. Men from all over the region, and sometimes further afield, descend upon the town to change this sporting event into a festival.

The event is essentially a rural one, relatively unsophisticated, traditional, lively and runs counter to more modern forms of entertainment. There are rules, apparently, though I was at a loss to discern any. If one camel declines to fight, its challenger is automatically declared the winner. If they both stand and fight, however, the winner is the animal that stays on its feet.

The contests are slow affairs, with each camel attempting to push the other backwards or to the ground. The camels are muzzled for the fight, so no serious injuries are inflicted. If a muzzle comes off during a fight, animals are bitten and make the most awful noise. Happily, this seldom occurs, and, like sumo wrestlers, winners and losers alike go home physically unscathed with only personal pride taking a battering

Prizes take the form of carpets given to winning owners, and although these are machine made, and inexpensive, they are still awarded and prized and signify that the contest has been fought and won. As one man said, “This isn’t about money, it’s about continuing something that was handed down to us by our grandfathers and their grandfathers.

In the evening, the camels are herded onto trucks or into pens for the night, and the revelry continues. Men play traditional musical instruments, drink Turkish raki neat, in large amounts, and accompanied by white feta cheese and lumps of ‘karpuz’ – water melon.

I stayed in a local ‘pansiyon’, woke with a hangover, ate a hearty breakfast of boiled eggs, olives, bread and tea, and later returned to the city of Izmir, to the noise and the rush of modern life, thankful to the camels and their owners for providing an entertaining diversion from my normal routines.

Robert L. Fielding